Yesterday, I wrote about my philosophy regarding creativity. I said that the best creative endeavours are not liked by most, but really, really liked by some. Today’s post is about a game you all probably will not like. But, if you are the kind of person who would like this game, then you will really really like this game.

Eastward is a game made by a Chinese1 game development studio, that came out in 2021. I played it in 2021. I just finished re-playing it, like, 20 minutes ago, because I got a Steam Deck and it seemed like a good game to play on a Steam Deck.

First, the polarizing sales pitch. Lots of people online do not like this game. I love this game. My best sales pitch for it is “this is slice-of-life anime, the game. If you don’t like slice-of-life animes, you will hate this game. If you do like them, you will probably love this game”. What is a slice-of-life anime? It is exactly what it sounds like, and my favourite kind of anime.2 A slice of life anime doesn’t really have a plot, just like our lives don’t really have plots. They have vibes. Aesthetics. Episodic moments.

For an example of one of my favourite slice-of-life animes, consider Girls’ Last Tour

Girls’ Last Tour is about two teenage girls who are alone in a post-apocalyptic wasteland that looks, aesthetically, as if World War 2 ended in nuclear armageddon. They travel the world in a Wehrmacht Kettenkrad, being two teenage best friends. That’s the whole plot. Maybe the story went somewhere in the episodes I haven’t seen yet, but, I kind of hope it doesn’t. Because I’m not watching this anime because I want to know what happens. I’m watching it for the vibes along the way.3

In fact, Girls’ Last Tour specifically evokes pretty vivid memories for me from when I was a teenager. I’d be walking home after school with my best male friend, we’d stop at the park along the way, and just sit on the swings for half an hour and talk about random shit.4 Because that’s mostly what happens in Girls’ Last Tour. They talk about whatever random shit is on their minds while driving through an aesthetic wasteland.5

Eastward feels like this. It feels so much like this, that there’s one chapter in the game that people online derisively refer to as “the anime filler episode”, a generally accurate take.

So if Eastward doesn’t have a plot, what is it about? Well, it does have a plot. A really dumb, really confusing plot, that is full of holes, and that doesn’t really matter to my enjoyment of it. Consequently, this blog post will be completely full of spoilers to this game. I’m going to speed-run the plot here just to have a point of reference, skip to the next <hr>6 if you don’t care.

John is a silent protagonist, a hobo who lives in an impoverished underground cave village, “Potcrock Isle”, where he, along with the other ‘diggers’, dig up ancient technology from a long-ago civilization on behalf of a despotic mayor who pays them in salt and constantly threatens them with violence. On day, he digs up what looks like a cloning pod that contains a young girl in it. He adopts this girl as his daughter, and names her Sam.

Sam has memories of a past life on the surface, remembering its lush greens and vibrant blues. But the mayor tells everyone that the surface is a wasteland where nothing but death awaits, and forbids anyone from riding the elevator to the surface, which still exists for some reason. One day after an argument at school, Sam sneaks into that elevator and goes to the surface. John goes after her to rescue her, and they come back to Potcrock. The mayor finds out and, after jailing them, condemns them to “Charon”, a mythological monster that the mayor uses to threaten the townsfolk. During this condemnation, we find out that Charon is a train, and the sentence they’re condemned to is to ride the train to the surface. This happens.

On the surface, they look out the train windows and see that Sam was right. It is a lush beautiful paradise. They eventually end up at the town of Greenberg, which seems like an idyllic farming village, with a mildly eerie feeling that it’s too perfect. Eventually, while helping out the villagers, Sam and John come across a bizarre advanced scientific laboratory, which automatically unlocks when it sees Sam. A robot inside refers to Sam as “Mother”, and activates a console that says it is “deploying the miasma”.

They return to that village but, late at night, are awoken by a mysterious cyborg ninja,7 who tells them that they must flee to the train station immediately because the miasma is coming. As they flee, the miasma starts catching up on them. If you get caught in it, your health is rapidly drained, implying very dark things about what it’s doing to the village.

In the nick of time, you get to the train station, and head Eastward8 to New Dam City. This is a city built on top of a dam, and seems to exist primarily so all the characters could make millions of dam/damn puns. It seems to be run and organized by a wunderkind named Alva, who is repeatedly referred to as the princess. Through sheer coincidence, the cyborg ninja, Isabel, is Alva’s ambiguous lesbian romance interest.

Sam and John spend some time hanging out in New Dam City, going on low-stakes episodic anime adventures, until they run afoul of Lee, the local mob boss and, it is eventually revealed, Alva’s adopted brother.9 Eventually, miasma attacks New Dam City, but Alva activates “the buddha fan”, a gigantic fan built into the dam, by her grandfather, which successfully blows the miasma away.

Soon, however, the miasma returns, and when they try to activate the fan a second time, they find it has been sabotaged by a punk kid named Solomon, who keeps screaming about miasma and Mother. The heroes seem to have saved the day in the nick of time, but something happens off-screen which results in Alva’s death.10

Alva’s death sends Isabel into a spiral of despair, and she flees New Dam City to travel Eastward to Ester City, a famed hub of science and technology, where Alva’s grandfather originally came from. Sam and John set off to follow them for, I honestly don’t even know why. They are joined by two other characters, William and his robot boy Daniel, who have periodically encountered our party before as basically scam artists. Further, various incidents happen between William and John implying they know each other. There was a man named William who had a son named Daniel, in Potcrock Isle, but William claimed to have visited the surface, and was exiled to Charon before the events of the story. It is heavily implied but never outright stated that this is that William.

While travelling Eastward, their train gets stuck in a time loop, and then crashes into another train, full of highly intelligent monkeys whose only drive in life is to create “Monkollywood”, making movies for the very unintelligent humans they have in cages. After messing about in this “anime filler episode” for a bit, we find another one of those high-tech spooky labs at the end of the train, run by a middle-aged guy named Solomon (odd, that; he has a similar outfit to the punk kid, too). Our heroes beat Solomon in a boss battle, winning an ancient rocket engine they can strap to the back of their own train car, to go fast enough to pass through the time loop.

They end up at Ester City, where they are once again stuck in a time loop. After three iterations of the time loop, they figure out the secret to breaking out of it: The city’s wise genius, an elderly scientist named Solomon (huh!), resides in the Eternity Tower, and in that tower, by confronting him, the time loop can be ended. So, Sam and John do that. The time loop ends, and we find out that it was just as much a simulation as a time loop; Ester City had long since been destroyed by Charon’s miasma. Oh, by the way, Charon, the train, is the thing that spreads the miasma.

Shutting down the time loop summons Charon, but this time it stops and lets Sam in, referring to her as “Mother”. John follows, into Charon, to rescue Sam. Inside Charon is a surreal environment that is half advanced tech and half fever dream, and we find that a sort of “Evil spirit” version of Sam has been orchestrating all of the cataclysm, but our real version of Sam has developed a separate “good spirit”, and is resisting this influence. We travel through “Charon’ss Museum”, which explains all of the plot to us, poorly: At some point in the past, humans created AI. This AI created human cloning, and is using this to speed up human evolution for whatever reason. It pumps out a new batch of clones, let’s them live for like a year, and then executes them all with miasma, using the data generated to make a better batch of clones.

We catch up to Isabel, who is attempting to use some of the cloning pods inside of Charon to create a new Alva. And then we have the final dramatic battle where, with John’s help, Good Sam first defeats, and then merges with, Evil Sam. This, somehow, ends everything. The world is saved, the cycle is broken, but nobody seems to remember what happened.

The final scene shows a now teenaged Sam waiting for a train at a station when she runs into a very obviously homeless, broken John. She doesn’t recognize him, but he recognizes her. The end credits roll.

I told you the plot was retarded

So why is this game one of my all time favourites? In short, excellent art and aesthetics, really interesting environmental story-telling, and the wholesome nature of John and Sam’s relationship.

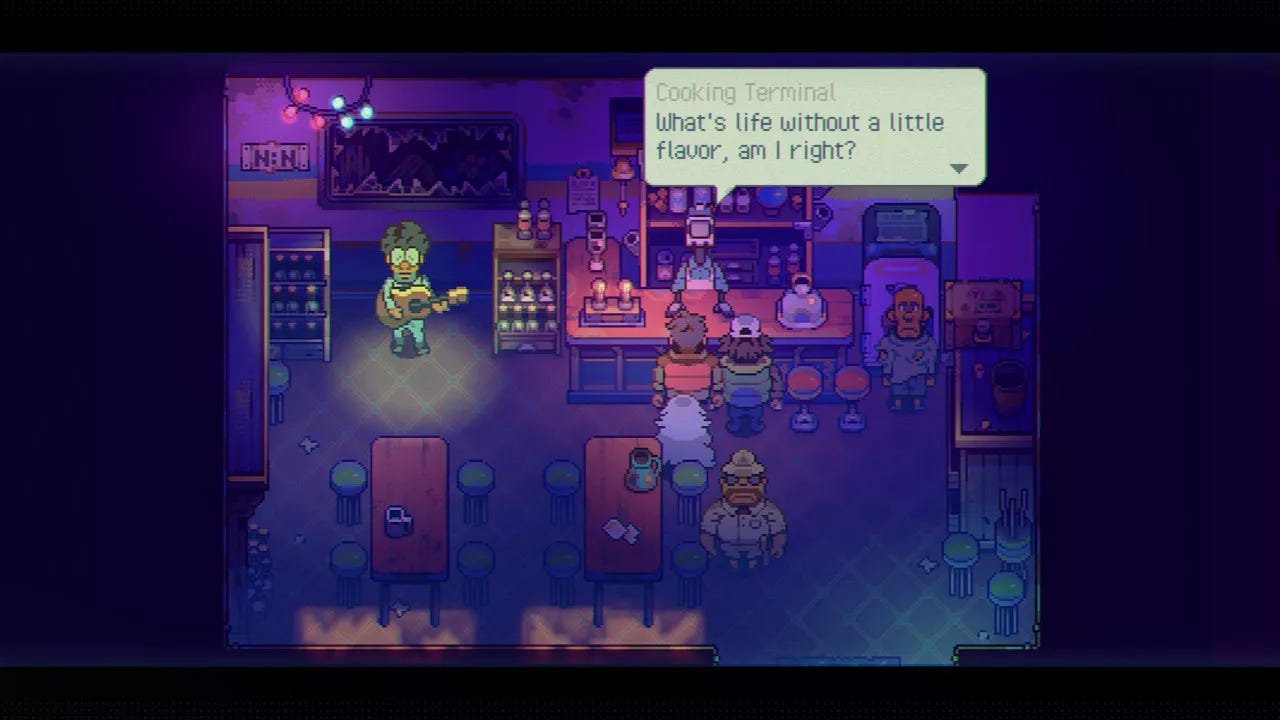

The first thing to call out is that this game is really, really aesthetic. Sure, the storytelling itself can be melodramatic at times, but it’s just really fun if you don’t it too seriously. For a great example, cooking is a major, important theme in this game. John’s primary weapon isn’t a gun, it isn’t a sword, it’s a frying pan, because John is an excellent chef. Cooking is the games crafting mechanic, combining ingredients to make various health-recovery dishes. It’s a major motivator in the ‘episodic anime’ New Dam City part of the game. And, it’s a core element of Sam and John’s relationship. I will get to that later, but for now, this image captures it perfectly for me.

And, of course, the song that plays whenever you’re cookin’, is very catchy

Which brings me to another wonderful aesthetic of this game: the refrigerators are how you save your game. And each refrigerator will give you a sort of ‘ancient Chinese wisdom’ proverb, phrased in terms of an elaborate metaphor between ‘leftovers’ and ‘memories’.

You place things in the fridge in hopes that they'll stay good forever. But the next time you open the fridge, they may have already gone bad.

Not my most favourite one, but I can’t find a list of all the quotes online and that was the first one I could find, to give you a sense of its feeling.

The Save Fridges are reminiscent to me of the Save Frogs from one of my favourite games of all time, Mother 3. And I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to say that this game sees itself a sort of spiritual Mother 4.11

To cap off the aesthetics portion of the argument, I present to you the opening cinematic when you boot the game. This perfectly captures the aesthetics of Eastward

The aesthetics and the environmental storytelling are almost the same thing, kind of. Both are fundamentally about attention to detail.

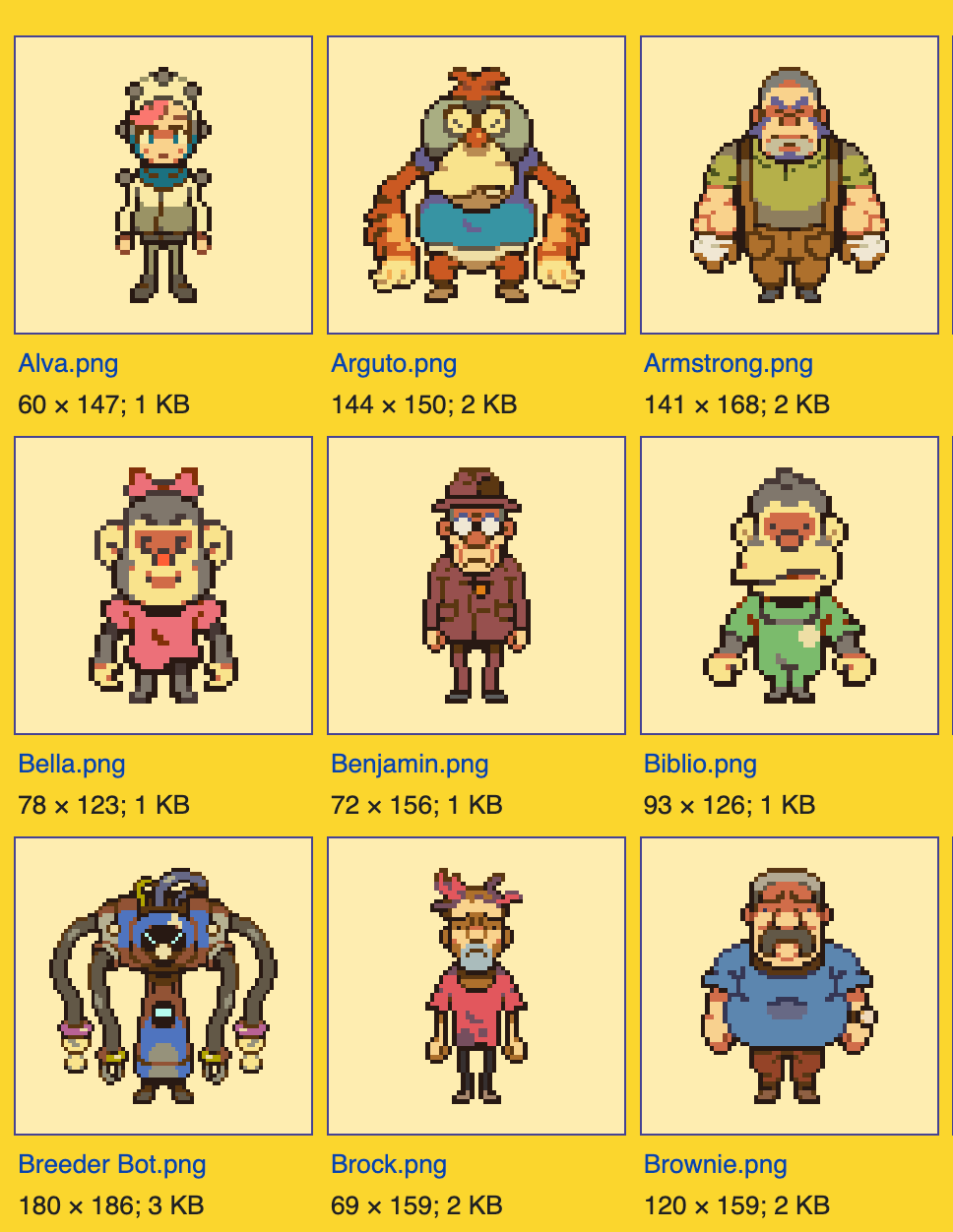

Take, for example, the NPCs12. There are a lot of NPCs. But they’re all well-written. They aren’t spouting random dialogue. Each one has a name, has a personality, has an aesthetic, and really adds to the feel that this is real world, not a game world

Generic townsfolk, these most certainly are not.

The attention to detail applies even to the main characters. Take John, for example. Sometimes, you’re in combat in this game. You might encounter monsters and have to swing at them with your frying pan. But sometimes, you’re not in combat and, of course, no civilized person would be swinging their frying pan around during peacetime. Instead, whenever you’re in an area without combat, John’s animation changes. He now runs around with his hands in his pockets.

This attention to detail even applies to the plot, at least a little bit. As I mentioned in a footnote, within Eastward is a game-within-a-game called Earth Born. If you play through Earth Born, and then pay close attention to some of the dialogue from various NPCs you encounter in the main game, you start to realize that the plot of Earth Born mirrors the plot of Eastward, and this helps (a little bit) with making sense of what’s going on. Various things that the Save Fridges say also foreshadow the plot, and re-playing it already knowing what will happen, gives a new meaning to a lot of the things they say.

The attention to detail is everywhere. The flavour text is delightful. This is the message you see when you cook a pizza in the game:

John once tried to make pizza. John once put pineapple on pizza. John failed at making Pizza.13

This is one of the reasons why I really like slice-of-life stuff. In a regular RPG, if you were to read a book, or talk to an NPC, or find any kind of written message in the game, it’s either going to be plot-relevant, an ambiguous hint for some secret, or bland and generic. But in this game, it’s not really about the plot. It’s not really about secrets. In this game, NPCs say what they say because in a real world, everyone would have something to say. Each and every character in this game, no matter how small their role, is intentionally there to add something to the universe. Not one person is unnecessary.

A lot of these details flesh out the world, too. Take William and Daniel, who I mentioned earlier. The first time I played this game, I wasn’t paying too close of attention to all the NPC dialogue at the start of the game, and so I had no idea that William we encounter in the game was a dude who used to know John back in Potcrock. Did this matter to my enjoyment of the game? Not a bit. It’s not at all relevant to the main plot (90% of which is just told to you directly, at the end of the game, Primer-style). But it fleshes out the world, and rewards you for paying attention to the details that, in other games, you would ignore. All of those details are wonderfully integrated into the universe in a way that adds a really fun colour, a dimension, to the universe that most other RPGs don’t have.

But the thing that makes this game so near and dear to my heart is the relationship between the main characters. John absolutely loves Sam. Sam absolutely loves John. They are the perfect picture of an ideal loving family, even as their whole world is falling apart. This is even a testament to the environmental storytelling and attention to detail I mentioned earlier. John is a silent protagonist, and various characters even make jokes about it, to him, in the game. He does not say a word. And yet, he doesn’t need to. His actions, his body language, shows that Sam is the most important thing in the world to him.

I think, without a shadow of irony or hyperbole, that John is one of the most noblest heroes of any hero in any game that I have ever played. He is the perfect embodiment of male virtue, what we should all aspire to be. He’s basically homeless, living in a burned out shell of a transit bus, but when he finds a little girl needing rescued, he shares his meagre life with her. When she runs off to the surface, a crime punishable by death,14 he could have just said "eeeh, not even my real daughter anyway”. But he doesn’t. He runs after her, fully knowing the consequences and accepting them. He does it in a heartbeat, because that’s the right thing, and John does the right thing.

There are times in the game when Sam is tired, or wounded, or unconscious. In these times, John carries her, piggy-back style. At one point in the game, Sam is wandering off alone in New Dam City while John cooks them dinner. She’s late for dinner, so he goes to find her. She’s fine, winning big with her lucky coin at the casino. But John wants to make sure she’s fine.

By the time we’re near the end of the game, the time loop ended and Ester City visited by Charon, John, as well as us the player, know full well the threat that Charon poses. But when Sam enters the train, John knows exactly what to do, and doesn’t hesitate. The game even emphasizes this, with a little cinematic

John is the ultimate hero. This entire game, he’s not even really the main character. He’s just a guy caught up in Sam’s fate, going along to make sure she’s ok. He’s not fighting for money, for power, for status. He’s not fighting to save the world, although he does as a side effect of the quest. No, everything he does in this game, every action he takes, is in service to a scared, lonely little girl, stuck in a nightmare, who has nobody else to save her. The world was better when this attitude was more prevalent.

That’s what makes the ending such a gut-punch.

John succeeded. He saved Sam. But after the final battle, they are separated, and Sam loses her memories. Years later, they encounter each other on the train platform.

Sam is growing up into a happy young lady, who has her whole life ahead of her. And John has grown old and forgotten, homeless, nothing but a tattered old shirt and a hobo bindle to his name. He remembers Sam, but as a silent protagonist, he can do nothing to jog her memory. He can’t even say hi. John was the most heroic character in this story, and his reward is that, once the day is saved, nobody needs him anymore, and he’s tossed aside.

But John doesn’t care. John did the right thing, and saved someone who needed saving. Somebody had to, and no one else would. John, good ol’ workhorse that he is, did his duty. Prosperous society is built on the backs of the people who do their duty. Not for fame. Not for power. Not for money. But because somebody had to, and no one else would.

I think this is a beautiful representation of the absolute best familial relationship that humanity is capable of. And, especially in 2021, when this game came out, where can you even see that anymore? I can’t even remember the last woman I met in my actual life who had a good relationship with her father, nevermind depictions thereof in media. No, the media is too busy girlbossing to let a father take the spotlight like that. And yet, John is the ideal father that all men should aspire to be. He doesn’t need a sword to slay dragons. He has a pan, to slay hunger.

It would be a little silly to write an essay about a game without at any point talking about gameplay. Now, the gameplay is pretty fun, but again, the magic of this game isn’t about the game, it’s about the journey. The gameplay is alright. Action-RPG style, kind of like old Legend of Zelda games. The various spaces that function as ‘dungeons’ strike a nice balance between not being too boring, and not being too confusing. There’s a handful of monsters, mostly you’ll just whack ‘em with your pan until they die.

Throughout the game, you’ll get three weapons, a regular gun, a fire gun, and a sawblade gun. The fire and sawblades are used for a handful of puzzles, and the regular gun hits for double damage compared to your pan, at the cost of using ammo, but ammo is pretty plentiful. You’ll also get three kinds of bombs, regular bombs (which you’ll mostly use to clear debris and find hidden paths), flying homing bombs (which are used for a handful of puzzles when you get them, and then promptly forgotten about by the game designers), and remote control bombs, which you get so late in the game that they might as well not exist.

There’s a bunch of mini-bosses you’ll encounter, that are more or less just the same kind of robot over and over again. And a handful of full bosses, aesthetically interesting but mechanically not; you’ll just whack ‘em a bunch until they die.

One frustrating game element of this game is that most of the secrets are missable, and if you miss them, you’re going to have to finish the game, unlock chapter select, and then re-play the entire chapter just to get them. This is a virtual necessity, given the structure of the game being based on fleeing eastward from the miasma, and the narrative would suffer if you could go back, but it’s still annoying. I missed exactly one key item in this second play through, it’s the same as the one key item I missed in my first playthrough, and I still don’t know where it is.

But like I’ve said a billion times already, if you’re a dick-stabber15, this game is not for you. If you’re looking for an exciting game, with interesting mechanics and gameplay, secrets to unlock, all that normal game stuff, Eastward is not for you. If you want a deep, interesting plot, that makes sense and has a point, Eastward is not for you.

If you want to escape for a dozen hours into a charming, lovingly designed universe, where every little creative detail is intentional, and your only reward is the friends you made along the way, then Eastward is very for you. What’s life without a little flavour?

To the best of my knowledge, all the best video games come from Japan, all of the most popular video games come from America, and all of the most wonderful, unique indie games come from singular mad geniuses in Europe. The only other games I’ve ever seen from China were gacha garbage.

“Gacha games” are games whose primary mechanics involve luck, and spending real world money to mitigate bad luck. They’re basically just slot machines where the prize is fake money instead of real money. For a while, a decade ago, I played one where I collected cats. I forget what it was called

Believe it or not, I do not really watch anime. I just pretend so my friends think I’m cool. I don’t really watch anything unless it’s in the background while I’m doing something else, and it’s difficult to read subtitles while doing something else. The only anime I’ve watched are either a) ones that have really good dubs; or b) ones that someone made a point of watching with me, so that watching was the primary activity instead of the background one.

And the vibes are unreservedly wholesome. Partly this is because, since they are more or less alone in the world, there’s no other people around to be evil. Partly, this is because they’re naieve teenage girls.

Incidentally, I think this is why a lot of ‘teenage girl’ anime appeals to young adult men. It’s not a sex thing (it probably is for some of them), but it’s like a, “the world is chaotic and stressful and evil, but for an hour I get to watch this world where everyone is happy and nothing bad ever happens” idea. It’s a yearning for the innocence we all lost from childhood.

This friend, when we were 15, watched Glen Beck obsessively.

This friend, in the late 2010s, very publicly ended our friendship over politics; he’s woke now.

He chose a higher-academia career path, and I’ve always interpreted this episode as him making a highly public demonstration of wokeness that, deep down inside, he didn’t believe, because his future income depended on it. Still hurt, and we haven’t spoken since.

Not as in “a place where there is nothing aesthetic”

But rather, as in “a wasteland that is particularly aesthetic”

<hr> is HTML for “horizontal rule”, and it’s the literal code that generates the horizontal lines I like to use to organize my essays

Not literally a cyborg ninja, although it is kind of implied that she is a cyborg, but “cyborg ninja” is an anime trope best exemplified by the character from Metal Gear Solid who is literally referred to as “cyborg ninja”

GET IT?!??!

Actually, Alva is the adopted one, but it doesn’t matter.

This is one of the single most complained about plot holes. We don’t see what happened. Technically, we don’t even know if she’s dead or merely injured. It doesn’t really matter. This is slice-of-life, if you’re getting hung up on plot details, this game is not for you

“Mother 2” is better known in the US as Earthbound. You’ve probably not heard of it before, but it is hands down one of the greatest games of all time. You have heard of its main character, it’s Ness from Super Smash Bros.

Aside from the really obvious that the main antagonist in this game is “Mother”, there’s another very obvious easter egg. Within Eastward, the children of the world all love playing this video game in the universe called “Earth Born”. Earth Born is a very obvious nod to Earthbound.

(N)on-(P)layer (C)haracters, which is self-explanatory

I think this particular fight is silly but if I had to pick a side, I’m going with team pineapple. I don’t even like pineapple that much, but pineapple on pizza doesn’t deserve the hatred it gets.

At least, as far as anyone knows when this happens in the game

Dick-stabber is a perfect euphemism for “completionists who obsess over unlocking 100% of the secrets in a game”. It comes from this old game dev podcast I listened to, where the game dev guy complained that, because completionists get so mad when they can’t complete something, it constrains his creative freedom and makes his content suffer.

The actual phrase comes from something he said, which is that “I could make a game where you could fuck the prom queen for 10 points, or stab yourself in the dick for 11 points, and you assholes would grab the knife immediately”.

No, pineapple on pizza deserves every bit of hatred it gets. It's a waste of both perfectly good pineapple, and perfectly good pizza. It makes the pizza *soggy*, and that's just unforgivable. If someone managed to make, like, dried, thin sliced, "pineappleroni" and put *that* on pizza, it could well be perfectly tolerable. 😁